James Cleveland Owens is born in Oakville, Alabama. The tenth child of Henry and Emma Owens, JC has six brothers: Prentice, Johnson, Henry, Ernest, Quincy and Sylvester, and three sisters: Ida, Josephine and Lillie.

James Cleveland Owens is born in Oakville, Alabama. The tenth child of Henry and Emma Owens, JC has six brothers: Prentice, Johnson, Henry, Ernest, Quincy and Sylvester, and three sisters: Ida, Josephine and Lillie.

Like thousands of black families throughout the South, the Owens are sharecroppers. As sharecroppers, a landowner allows them to live on their property and use farm equipment in exchange for their hard work and half a season’s crop from the land they farm. The Owens sell the remaining half of the crop and with the little money, buy clothing and essentials.

JC is a small and sickly child. It is a trial to nurse him through one cold winter after another, especially since his father, Henry, cannot afford to buy any medicine or pay a doctor. Little JC is wrapped in soft cotton feed sacks in front of the stove. He coughs, sweats and cries, sick with pneumonia for weeks at a time. As if that is not enough, terrifying boils appear on JC’s chest and legs. His father holds the crying child while his mother practices surgery in her own home, carving the boils out of his flesh with a red-hot kitchen knife. Through sheer will and the determination of his long-suffering parents, JC somehow survives these brushes with death. By age six, he is well enough to walk the nine miles to school with his siblings.

JC is a small and sickly child. It is a trial to nurse him through one cold winter after another, especially since his father, Henry, cannot afford to buy any medicine or pay a doctor. Little JC is wrapped in soft cotton feed sacks in front of the stove. He coughs, sweats and cries, sick with pneumonia for weeks at a time. As if that is not enough, terrifying boils appear on JC’s chest and legs. His father holds the crying child while his mother practices surgery in her own home, carving the boils out of his flesh with a red-hot kitchen knife. Through sheer will and the determination of his long-suffering parents, JC somehow survives these brushes with death. By age six, he is well enough to walk the nine miles to school with his siblings.

School amounts to a one-room shack that doubles on Sundays as the Baptist church for the blacks of the area. The teacher is anybody who has the time and inclination to teach. During spring planting at harvest time, students work the fields instead of arithmetic problems. In spite of all the drawbacks and interruptions, JC learns to read and write.

Despite hard times JC found time for play. In the low hills of Alabama, JC begins to run. He recalls that even though he was thin and sickly, “I always loved running. I wasn’t very good at it, but I loved it because it was something you could do all by yourself, under your own power. You could go any direction, as fast or slow as you wanted, fighting the wind if you felt like it, seeking out new sights just on the strength of your feet and the courage of your lungs.”

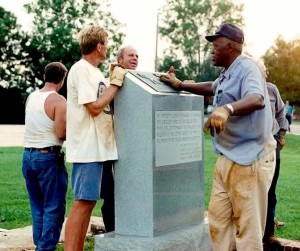

The original monument that stirred controversy in 1983, when the all white Lawrence County commission refused to put it on the courthouse lawn. Instead it was erected six miles away in a tiny community, tucked away for few to ever see. Later that same year vandals with a chain hooked to a truck tried to pull down the monument and local residents ran them off. It has been relocated to its permanent home on the grounds of the Jesse Owens Memorial Park and Museum.

In 1983 a proposal was brought forth to honor the famed Olympian by placing a monument on the courthouse lawn. It was blocked by the all white County Commission, stirring up controversy, but Oakville residents wouldn’t give up on the Owens monument. A 1983 Gadsden Times article read, in part: “Three Lawrence County Commissioners deny race had any bearing on their decision to ban a monument honoring Olympic star Jesse Owens from the courthouse lawn. During a special meeting, three county commissioners voted to block Rep. Roger Dutton’s proposal to put the monument on the lawn. One commissioner abstained.” It went on to read… “The three commissioners who voted against proposal – Wayne Sutton, Oakley Lanier and Raymond Beck – denied race was a issue. Sutton and Lanier said there were too many monuments on the square, which includes the courthouse, lawn and parking lot. There are memorials honoring veterans of WWII and Vietnam. Beck said he is opposed to honoring individuals. ‘We have veterans of wars and they should be recognized,’ Beck said.”